Female work between manufacturing and commerce in 18th-century Trieste

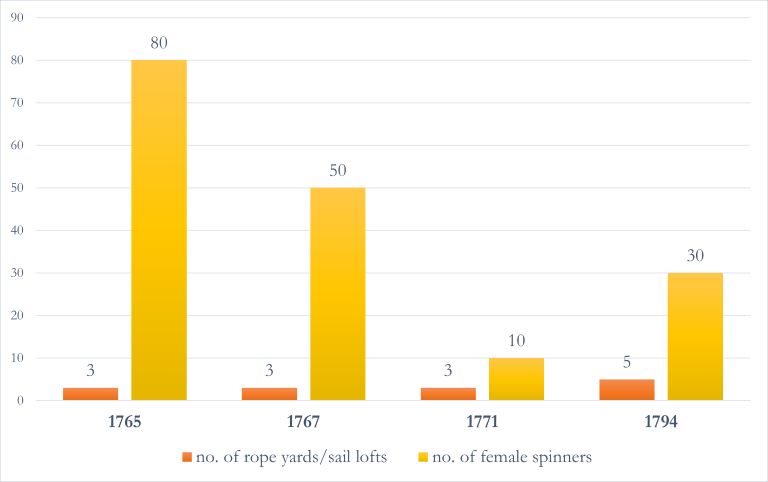

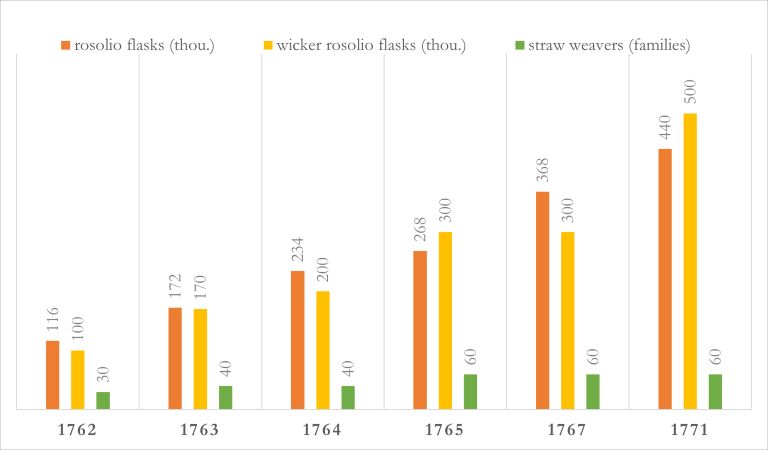

In Trieste during the 18th century, the female workforce represented a large part of the multifaceted working population that contributed to the growth of the city and its port, which, over a few decades, became one of the greatest Mediterranean emporiums. Although the sources do not reveal their direct involvement in navigation, women were engaged in many activities related to the maritime sector. For example, they worked on the construction of port infrastructures, the production of the equipment needed to arm the ships, and, finally, the manufacturing of strategic products for commercial flows. This female working class may be represented by workers such as Mariuza Talich and Antonia Calich, who transported by wagon stones to construct the piers, or by the 70 spinners employed in the Buzzini Brothers’ sail loft during the 1760s. In the second half of the century, “rosolio” had become one of the leading export goods. More than twenty distilleries were active in the city, exporting hundreds of thousands of “fiaschi” (i.e., bottles covered with a close-fitting straw basket) every year. Rosolio bottle straw baskets were made primarily by female workers. That working activity had taken root in the city around the 1750s. By circumventing the rules that favoured the purchase of glass produced in Bohemia (Habsburg Monarchy), Trieste’s merchants bought the flasks in Murano (Republic of Venice). Still, from the domains of the Serenissima – from Cavarzere specifically – even the straw to cover the flasks came. In addition, from Murano to Trieste, women specialized in the flasks’ straw-covering techniques, and they were also responsible for training other women in this craft.

4.3.a

A Young Port

(L.F. Cassas, Trieste Harbour (1802), Victoria & Albert Museum)

4.3.b

The Free Port and Immigration

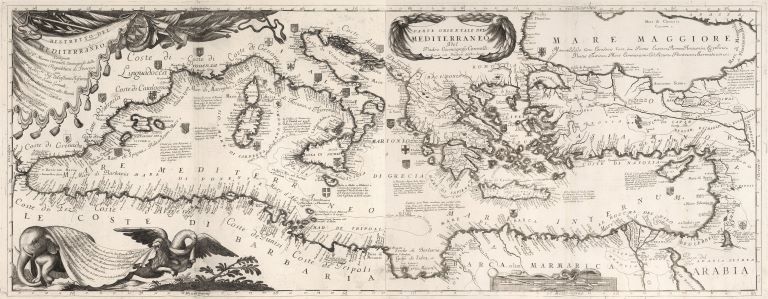

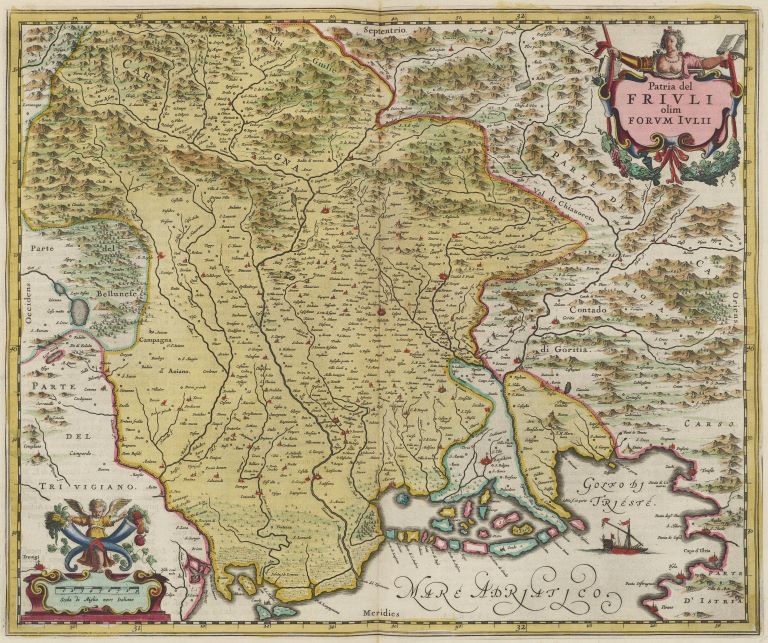

With the declaration of the Free Port in 1719, Trieste began to attract women and men who came to the city to evaluate the opportunities it offered. Some stayed indefinitely. Others stayed for shorter or longer, but always limited, periods of time. Thus, Trieste began to be populated by people of different beliefs and languages, coming from the hinterland, the Levant, the Italian Peninsula, the Balkans, and Europe.

(V. Coronelli, Mediterraneo (1693), DRHMC-SU)

(J. Blaeu, Patria del Frivli olim Forvm Ivlii (1665), DRHMC-SU)

(J. Blaeu, Istria olim Iapidia (1665), DRHMC-SU)

4.3.c

A Young Woman from Istria

(J. Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, Femme de l’Istrie (1787), WDPC-NYPL – Digital Collections, ID 827333)

4.3.d

Female Spinners in Trieste

(D. Andreozzi, Gli urti necessari, in Storia Economica e Sociale di Trieste, vol. 2)

4.3.e

Trieste Fashion

(Particolare di Nouvelles modes de 1797: Coiffure a la bonne fortune, Rijksmuseum, via Europeana)

4.3.f

Rosolio Wicker Flasks

From the mid-17th century, heavier distribution of refined sugar was followed by greater production of rosolio, especially in the Italian peninsula. In the second half of the 18th century, Trieste had numerous distilleries that produced rosolio, especially for the foreign market.

(L. Baugin, Le dessert de gaufrettes (c. 1630), Musée du Louvre, via Wikimedia Commons)

(D. Andreozzi, Gli urti necessari, in Storia Economica e Sociale di Trieste, vol. 2)

(Collezione Dino Cafagna)

4.3.g

A Female Street Vendor (venderigola)

(M. Stifter, Marktszene in Triest, 1889)